Two things have me thinking about interpretation. The first is the set of responses I continue to get to Martin the Marlin, about which I wrote here. The second is the experience we recently had selecting an image for an email marketing piece. Let’s start with the book.

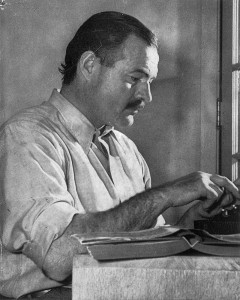

All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know. (Ernest Hemingway)

When I wrote Martin the Marlin, I had one intention: Write a good story. To qualify as good, the book needed to be an enjoyable read, it had to contain a lesson, and it had to convey the power of friendship, as well as hope for overcoming adversity. Did I draw on my own experience? Not in any conscious way. I’ve never had a close friendship with a fish, nor have I ever spoken with one at length; although, it’s not for lack of trying:

“Have you always known how to swim?”

“Gurble.”

“How many times have I told you not to blow bubbles when you’re talking?”

An adult once asked me if I was ever confined — physically or emotionally — as a child; and, if so, is that what made me write about a fish confined in a tank? There are three answers: (1) Anyone who experienced any trauma in childhood could make an argument for answering yes, but I had no such awareness as I was writing the book. (2) A question like that probably convinced Sigmund Freud to re-evaluate his initial ambition to be a plumber. (3) Please read this book.

It was my job to finish the manuscript and publish the book. It’s not my job to determine how anyone might interpret it. That’s the job of the reader and the beauty of perception and interpretation. As Grandpa O’Brien loved to say, “That’s what makes horse racing.” (For more on the act of reading, the highly curious might want to read this book, this book, or this book.)

I love to leave the interpretation of my music up to the listener. It’s fun to see what they’ll say it is. (Erykah Badu)

That brings us to the email marketing piece: We selected an image of a computer resource center in a college since the client was selling software to colleges. The client selected an image of a science lab.

Was either of them objectively right or wrong? No. Both were matters of interpretation. Since none of us has any idea what anyone will interpret from any image — ever — kibbitzing over it would have been a moot exercise.

All things are subject to interpretation. Whichever interpretation prevails at a given time is a function of power and not truth. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

Besides, images suggest what we mean. Words say what we mean. We often spend more time thinking about imagery than we do about language, about the message, about clarity, about saying to people what they want to hear in the way they’re most likely to hear it and respond favorably to it.

This is the lesson of social media: Imagery doesn’t constitute content, language does. Web bots don’t crawl pictures, they crawl words. The responses of email recipients aren’t determined by pictures, they’re determined by words — the truer and more persuasive those words the better.

Hemingway had it right. Make the sentence true. The rest will take care of itself.

—

Image in the public domain, via Wikipedia Commons.