As regular readers of my routine ravings know, I’m no fan of bureaucracy. Neither am I a fan of obfuscatory jargon. My education in the liabilities of both was well-earned. Herewith, a story from my days in the belly of the beast.

While dutifully serving one of the world’s largest insurance and financial services corporations (I still love that kind of talk), I was assigned the project of creating a piece of marketing collateral. (I love that kind of talk too, implying, as it does, collateral damage, of which there’s always more than enough to go around, not the least of which is financial.)

The project took place in the halcyon days of fiscal irresponsibility, in which companies accustomed to making money hand over fist hadn’t a clue about what they were making and how — or what they were spending and why. It was also a point at which the company for which I labored had the luxury of owning, staffing, and operating its own print shop. (See the first sentence in this paragraph.)

To my department, of course (and every other), the print shop was a cost center (another of my favorite bureaucratic terms). For the uninitiated, that meant my department had to pay the print shop (yes, they were parts of the same company) for its services, so that after my department blew its money, the print shop could blow my department’s money in whatever way it wanted. If this strikes you as being a daisy chain with funny money, trust your instincts.

Lesson One

Because there were more than enough meaningless jobs to go around, the print shop employed account people. These were the lackeys that lackeys like me had to go through to create the impression we were getting something done. The account person assigned to my project was named Dan (Lackey A), a sober bureaucrat, born to his invisible anonymity.

I submitted the job to Dan.

In those pre-digital days, the job consisted of a series of boards, on which type and images were pasted by a graphic designer. The boards were photographed and then electrostatically burned to metal plates. The plates were affixed to rollers on an offset press and inked. The paper was fed into one end of the press. The sheets came out the other end. They were dried, scored, folded, bound, stacked, and shrink-wrapped. Then the job was delivered to the client (Lackey B.)

When the job arrived in my department, there was a clearly discernible, fairly sizable, ragged-edged spot in the cover image of every piece in which there was nothing. No ink. No remnant or hint of the image. Just a kind of blank blob. It looked like an amoebic attempt at transparent geometry.

I immediately called Dan to report the matter.

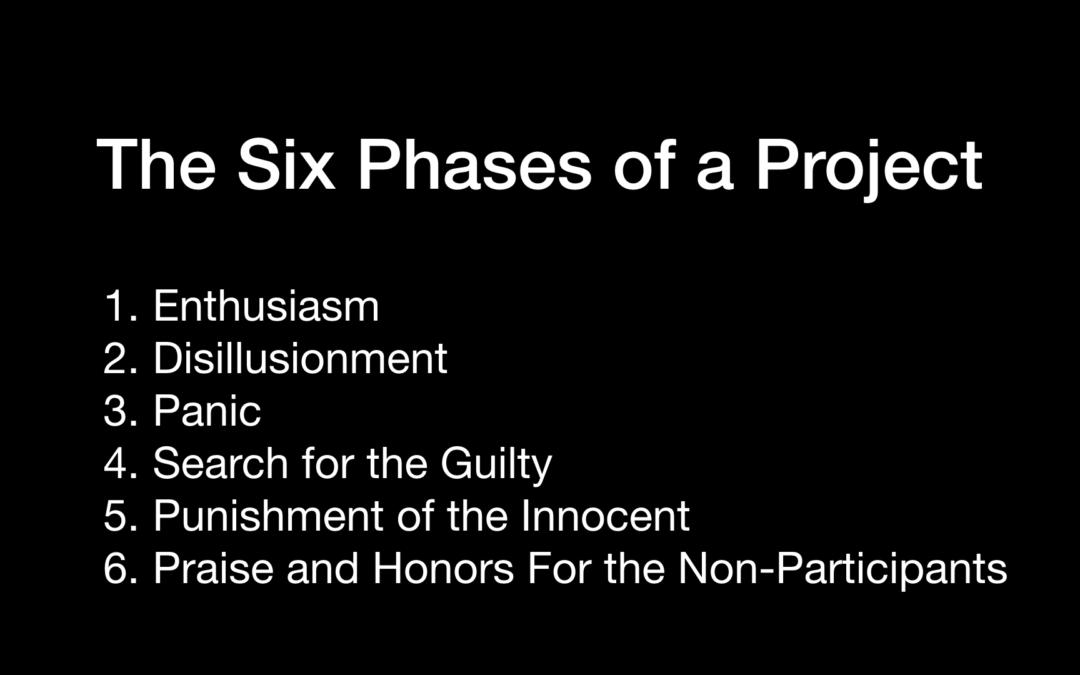

As it still does in every bureaucracy, my call resulted in the convening of a circular firing squad, which bureaucracies call meetings. We all spent the evening before the meeting getting our index fingers in shape, the better to point at each other the following morning.

Lesson Two

At eight o’clock the next morning, we assembled in the conference room in my department. Those in attendance included Dan, Dan’s boss, yours truly, my boss, Dan’s assistant, the pressman, the graphic designer, the Seven Dwarfs, the cast of Thirtysomething, and former WWE referee, Earl Hebner.

Desperately clinging to the quixotic hope the debacle could be concluded with the minimum number of casualties, I thanked everyone for coming and addressed Dan, doing my level best to retain a modicum of bureaucratic decorum:

Me: Do we have any idea what happened here?

Dan [in a voice not unlike Kermit the Frog]: It looks like something went wrong.

Me: Thank you, Dan. Now that we have that so cogently delineated, what is it, do we think, that went wrong?

Dan: It appears the image was marred somewhere along the way.

Me: Keenly observed, Sir. Now I understand your reputation for being a crack problem solver. Do we have the vaguest inkling — no pun on ink intended — as to what might have been the genesis of said mar?

Dan: I imagine something occurred between the time the boards were photographed and the plates were burned.

Me [turning to the rest of the people in the room]: And that, my esteemed colleagues, is why our man Dan here is reputedly known as the Sherlock of the Sheetfeed, the Poirot of the Press, and the Columbo of the Colophon. But I have another question, Dan: Are we able to determine the precise nature of that something?

Dan: Yes. There was a contaminant on the negative that was inadvertently introduced during the electroplating process.

Me: Beautifully stated, as always. But for those of us in the room who may not be fluent in the taxonomy of your particular discipline, Dan, can you please tell us what in the precise hell it means to say there was a contaminant inadvertently introduced during the electroplating process?

Dan: Somebody left a wad of masking tape on the negative.

Herb [slamming his right hand on the table three times]: 1! 2! 3! And, ladies and gentleman, your winner by way of pinfall, wrestling out of the blue corner, Lackey B!

Me: Take it easy, Herb.

Dan: Shoot. What a gyp.

Me: I love the smell of inanity in the morning.

Denouement

You might guess what happened next: In the short term, the print shop had to re-print the job at its own expense (translation: with the phony mazuma we’d already “paid”). The VP who originated the project decided not to use the pieces after they were done, even though they were perfect and exactly what he’d asked for. And I got to keep a piece of original artwork from Douglas Fraser, whom the VP who originated the project had paid $3,500 for the commission. (It remains framed in my office to this day.)

In the longer term, several other things happened, in this order: The VP who originated the project, spent all the money, then decided not to use any of what he’d had created faced no consequences. Dan was shit-canned. The print shop was shut down. I was shit-canned when my entire department was wiped out in a single stroke of the bureaucratic Bentley. And I still breathe sighs of relief every day.

Bureaucracy is just a contaminant on the negative.