During a recent visit to the Infinity Music Hall & Bistro in Hartford, Connecticut, to see and hear Marc Cohn perform, I ran into a friend, who happens to be an architect. That led to a later discussion with Anne Bjorkland* about the depressed market for commercial real estate in Hartford. Anne likened it to present-day Detroit; that is, so many commercial buildings now stand vacant since the businesses that formerly occupied them have been taxed, regulated, and otherwise bamboozled out of existence.

That led us to idle speculation about whether the auto industry ought to consider a move to Hartford. The speculation led to some homework on the subject, which led, in turn, to two rather surprising discoveries.

The first was the fact that one Albert Augustus Pope had actually begun producing electric automobiles in Hartford in the late 19th century. (Take that, Chevy Volt!) In May of 1878, Al met with George Fairfield, president of Weed Sewing Machine Company in Hartford, to ask about about making bicycles in George’s plant for Al’s company, Pope Manufacturing. Since the sewing-machine business was sucking wind at the time, George went for it.

By 1896, Pope Manufacturing was the leading producer of bicycles in the United States. Then, in 1897, Al asked George if he’d consider manufacturing cars. George said, “Sure. What’s a car?” Al drew George a diagram, and by 1899 the company had cranked out more than 500 electric vehicles.

Later that year, Al spun off Pope Electric Automobiles as the Columbia Automobile Company, which was then acquired by the Electric Vehicle Company. But with sales flagging due to the popularity of the internal combustion engine — and having no idea someone would come up with a hare-brained idea like Cash for Clunkers that would give the electric-car market false and fleeting hope — Al bailed out of the business, declaring bankruptcy in 1907.

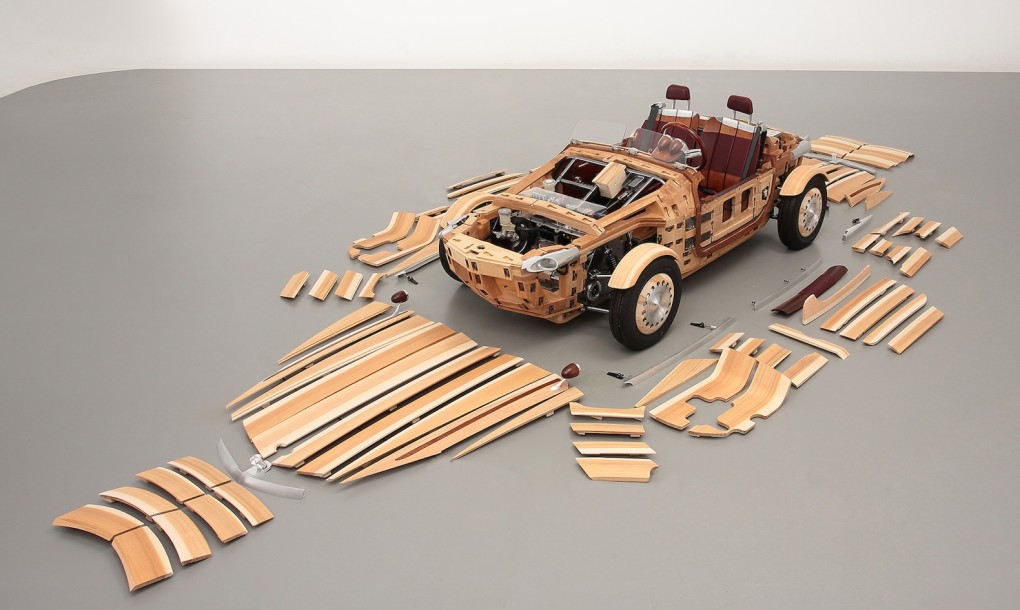

The second and more surprising discovery was the story R. Herbert Hart, the entrepreneur and fledgling auto magnate for whom the city of Hartford was named. Herb built a plant to make the do-it-yourself kits for wooden cars shown at the top of this post. He planned to call the cars The Herb. But Albert Murfwhiffle in Hart’s Marketing Department suggested he call it The Charter Oak; although the reasons for the suggestion are lost to history. But Herb’s plan had a fatal flaw:

Herb believed he had a source of cheap labor in the growing number of Dutch settlers coming into Hartford. (The Dutch settlement, Ford Goede Hoop or the Hope House [Huys de Hoop] was abandoned by 1654 after a failed attempt to turn it into a spelling school. But its neighborhood in Hartford is still known as Dutch Point.) Herb believed the Dutch were skilled at woodcraft, given the fact that they’d once worn wooden shoes. But he failed to notice the settlers were already wearing leather shoes, a consequence of their wood supply having been claimed by Dutch Elm Disease.

Since the British settlers who followed the Dutch to Hartford were preoccupied with colonizing most of the rest of the east coast, one of Herb’s few remaining options was to hire Lenape tribesmen to work in his plant. But they were still so miffed at Peter Minuit for having swindled them out of Manhattan for 24 bucks worth of trinkets, they immediately went on strike, causing Herb to shut down operations. (Herb subsequently founded The Hartford Insurance Company after he sold the Lenape the first commercial crime policy.)

So, there you have it. An evening of wonderful entertainment and pleasant conversation that led to a history lesson. I lead a charmed life, indeed.

* Hat tip to Anne for the exhaustive and precisely detailed historical research that went into this post.

—

Image courtesy of engadget.com.