On October 4, 1994, guitarist Danny Gatton was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his home in Newburg, Maryland.

In early 1989, some friends and I had the privilege of seeing and hearing Danny Gatton play in Hartford, Connecticut. It was a cold, snowy Friday night. Danny and his band had played in New York City the night before. The weather had kept them there longer than they’d planned. As a result of their late departure from New York and the treacherous congestion on the Connecticut Turnpike, they arrived in Hartford an hour or so after the show was supposed to have started.

No one who’d braved the storm to see them had left by the time Danny and the band reached the Summit Hotel. After briefly sizing the place up, the four men carried in their own equipment and set it up in the claustrophobic lounge. No fanfare. No roadies. No glamour. No pretense. No supper. No complaints.

After a cursory tuning and no introduction, Danny turned to his bandmates and said the name of a song (we didn’t need to hear it), the structure of which his rhythm section might loosely follow for the next three to fifteen minutes or more — or for as long as Danny might happen to be in the thrall of any particular muse. It didn’t matter. After counting off time, Danny ascended on the first of the evening’s innumerable flights of brilliant, beautiful, breath-stealing improvisation.

If there was a song-list for the performance, it was never relevant in the slightest. Each selection had a beginning. We knew that because we heard Danny count. Some even had lyrics, so those compelled to measure structure in linguistic coherence might be comforted. Aside from those two concessions to convention, the balance of the performance was a cross-section of Danny Gatton’s aural and technical imagination, a thrill-packed sluicing of the unbridled musical conduit he was.

After the show, we approached Danny at the bar, fully expecting to find him with little friendliness and less time — tired, hungry, probably sullen, and ready to be left alone. We were wrong. Danny was affable and unassuming, perhaps unknowing of the enormity of his talent and what it would cost in the end, perhaps knowing full well and grateful for the distraction we provided. In any case, he was casual and talkative, comfortable with us, as all strangers are in the common need of the barroom. I asked him only one question: “With talent like that, how come no one knows about you?”

Danny laughed without bitterness and gave only one answer: “Nobody understands this shit.”

By this shit, Danny meant the talent, the stylistic stew, that defied categorization and, so, resisted pigeon-hole approaches to branding him as a commoditized type by those who presumed responsibility for marketing his music. (“He’s country. No, he’s rockabilly. No, he’s jazz”, etc.) I continue to be haunted at wondering if Danny knew then how frighteningly and tragically right he was. Except for the initiated — his die-hard, see-him-perform-at-all-costs fans — nobody did understand. Least of all, perhaps, Danny.

Danny Gatton’s was a talent as rare, accidental, and dark as any talent given without the capacity to comprehend it. His myth will hold that he was playing by age two and that, by age ten, several instructors had advised Daniel (Sr.) and Norma Gatton to save the money they were spending for their son’s lessons. Danny couldn’t and didn’t need to be taught — he was capable of simply hearing something once and playing it. For embellishment, he was able to translate the wanderings of his imagination into the free-fall of his fretboard explorations. Un-asked for and never understood, Danny Gatton’s enormous talent existed, for him, to be coped with.

Obvious comparisons obtain — Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Mike Bloomfield, et al. — musicians and chronological peers of Danny Gatton, victims of their own hands and talents, however inadvertently or indirectly. But a non-musical personality, whose fate was determined just a year after Danny’s, offers a further, darker, and more instructive parallel: O.J. Simpson.

Like Danny Gatton, The Juice was possessed of a talent arguably bigger than he was. He was given the ability to carry a ball with uncanny grace, speed, and style, fleetly eluding big men who tried to maim him as he did so. He ran surely, instinctively, eyes darting and feet moving to the arcane rhythms of his heart and soul. Some of those rhythms were athletic. Some, it is still alleged, were not.

Likewise, Danny Gatton played guitar with inimitable inventiveness and abandon, deliberately eluding big men who tried to classify and package him as he did so, voicing the sweetness and spasms of melody and dissonance that moved him. (For ample doses of that melodic sweetness and manic dissonance, listen to the Jackie Gleason composition, “Melancholy Serenade”, from Danny’s 1987 album, ironically entitled, Unfinished Business. Forward to about 10:07.) He played surely, intuitively, eyes closing and fingers flying to the arcane rhythms of his heart and soul. Some of those rhythms were musical. Some, we now know sadly, were not.

Both these gifted men lived with and within packaging machines, professionals determined and processes intended to make them appear to be beings they were not, to make the two of them marketable, likable, bankable commodities for the bigger commercial interests that sought to control and profit by them. Neither was what he was trying to be made to be; neither was ultimately manipulable:

The Juice was never an affable celebrity, basking in the life-long afterglow of athletic success. He was seething, jealous insecurity, apparently waiting to erupt in the absence of having known himself. Danny was never a one-style wonder, blithely branded and blissfully bound by the marketing types who would otherwise have steered him numbly and narrowly toward their own visions and versions of success. He was silently suffering insecurity, tragically waiting to end the commercial world’s inability to recognize — and to accept in unfettered fashion — his genius.

Danny Gatton was never predictable, never classifiable by genre or style. (Guitar Player magazine’s Reader’s Poll named him Best Country Guitarist three years running. No one understood that less or suffered for the absurd narrowness of that designation more than Danny.) He was, rather, a husband, father, and antique car collector/mechanic, hoping that he and the world could come to terms with the music that found its way through him. Neither man knew contentment. In the end, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of taking the lives of two others. Danny Gatton was convicted of taking his own.

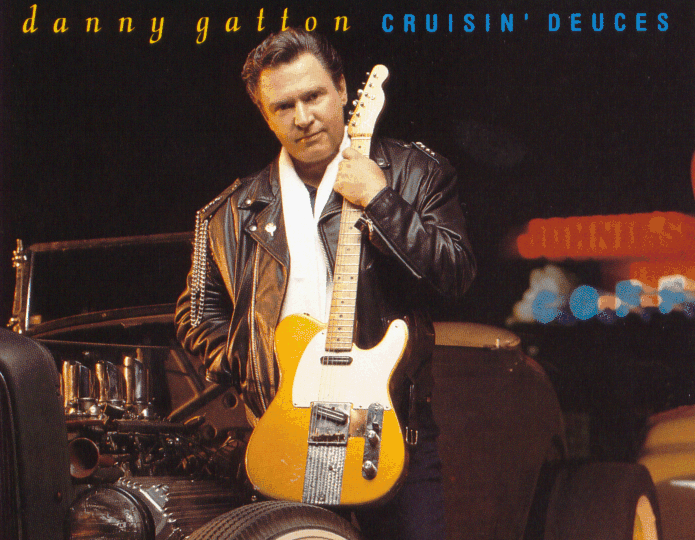

As news of Danny’s death gave music momentary pause in hushed surprise and futile wonder, sales of his records peaked modestly. Specialty shops received requests for his handful of independent-label releases. Cut-out bins were raided for 88 Elmira Street and Cruisin’ Deuces, the two albums Elektra let him complete before canceling the five remaining on his contract (arguably because they didn’t understand that shit). Then interest waned, and so did Danny’s brush with posthumous notoriety. All of that will matter as little as the structure of the songs he performed.

Danny Gatton’s gone now; and outside of his family — and a small and ever-shrinking world of guitar-players, music-lovers, and those with the strength to know and have faith in that which they cannot comprehend — he may one day, sadly, be forgotten.

He took with him a talent as dark as light, as pure as curiosity.

—

Image courtesy of allmusic.com.