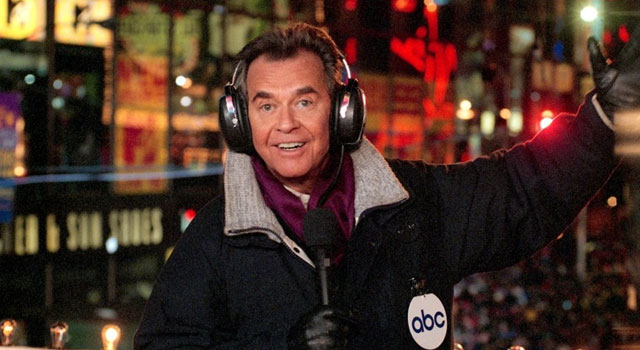

Dick Clark has been gone almost four years. But his past — the origins and ethnic derivations of the celebrity entrepreneur and perennial New Year’s Eve fixture — remained stubbornly murky … until now.

According to Clark’s Wikipedia profile, he was born Richard Augustus Wagstaff Clark Jr. in Mount Vernon, New York, in 1929. But according to a background check performed by CON (Celebrity Origins Network), he actually was born Salvatore Rubinaccio in Campobasso, Italy.

He was shipped to the U.S. in a crate of olives grown by his uncle, Giovanni. (Most people assume olives ship in the jars and cans in which they’re purchased.) Young Salvatore arrived in New York City in 1933, the year The Lone Ranger began a 21-year run on radio. (Salvatore would later claim that, had he been born earlier and gotten to the U.S. earlier, he could have played the Ranger’s loyal sidekick. And instead of being a Native American named Tonto, the character would have been an Italian kid named Vinnie; however, most entertainment scholars consider that a rumor or a delusion.)

By the time Salvatore was five, his uncle Vittorio (who’d left Italy in 1925 after a land dispute with his brother, Giovanni) had gotten him an agent who’d begun discussions with WNWY, the local cable-access channel, for a new weekday afternoon music/dance program, tentatively titled, Italian Bandstand. Thinking Salvatore Rubinaccio might be too ethnic a name for mainstream American audiences, the agent suggested Salvatore change it. Salvatore filed court papers and had his name legally changed to Samuel Rabinowitz, at which point his agent dropped him and WNWY stopped calling.

In November of 1939, after banging around for five more years, Salvatore (now Sam) learned an Italian-American kid had joined the Tommy Dorsey band. Frank Sinatra (original name, Francesco Sinatorrio) was an instant sensation. And Sam thought Sinatra’s success would pave the way for his own success as a singer. Wanting to return to his Italian ethnicity, but believing his former agent had been right about Salvatore Rubinaccio being too much for American tastes, Sam went back to court and changed his name to Sal Rubio.

Since Sal’s ears weren’t as big as Sinatra’s, and since he didn’t want to directly mimic Sinatra’s popular-music style, he realized he’d have to record a different type of music and adopt a different look. Showing signs of the keen judgment that had marked his career to date, Sal decided to perform country music and to fashion his look after The Man in Black.

After writing and recording his first single — “You Can Put Me in Jail (But You Can’t Keep My Face From Breaking Out)” — Sal didn’t work for the next 18 years. But in August of 1957, two serendipitous events took place: In the first, Sal, still wearing his Johnny-Cash-style pompadour, was having lunch at a Philadelphia lunch counter. One of the patrons remarked, “That dude looks like a slick narc.” Sal, whose hearing was compromised by dishes clattering in the close quarters of the little place, thought the patron said, “That dude looks like Dick Clark.” So, Sal changed his name again.

In the second twist of fate, Philadelphia’s WFIL-TV fired Bob Horn for drunken driving and accusations of running a prostitution ring. To replace Horn on the popular afternoon program he’d been hosting — which was (ironically or Divinely Providentially) a spin on the earlier, ill-fated Italian Bandstand concept — WFIL decided (completely arbitrarily, by all accounts) its next host should have the ethnically neutral name, Dick Clark.

The rest, as they say, is history … or at least the heretofore little-known version of it.

New Year’s Eve may never be the same.

—

Photo: Donna Svennevik / ABC, Inc.