Hunter Thompson died by his own hand nine years ago today. I found out at about 10:00 the next morning. Despite my brute incomprehension of what I was reading, it struck me as a rather Thompsonesque moment: It was snowing — bleak, cold. I’d gone to my browser’s home page to check the local weather forecast, and Thompson’s death was one of the AP headlines.

My first thought was of reading Thompson’s work, of all the reverent conversations I’d had with friends and colleagues about Thompson’s incisive intellect and his ruthless honesty. Those memories stay with me always. The fact that we often idealized his work — that it made us wish to be possessed of the same kind of apocalyptic voice, to be the same kind of incendiary conscience — sometimes haunts me.

Nixon was so crooked that he needed servants to help him screw his pants on every morning.

My second thought was of the price exacted from those endowed with such prophetic voices, visions, or propensities. In our conversations, my friends and I had talked about the likelihood that Thompson would have been killed had he lived in another place or time. We never extended that topic to the likelihood that it becomes impossible to live — like Jesus, Socrates, Chet Baker, Frederick Exley, and Jerzy Kosinski, or those minced by the celebrity machine like Jimi Hendrix, Heath Ledger, Michael Jackson, Amy Winehouse, Whitney Houston, et al. — when one is possessed of such voices, visions, or propensities.

Absolute truth is a very rare and dangerous commodity in the context of professional journalism.

It’s not the possession that undoes the possessed. It’s the things neglected, sacrificed, or disdained in deference to the possession that conspire to take them from lives so singularly unbalanced. It’s easier to withdraw than it is to reach out. It’s easier to scorn than it is to accept or to be accepted. It’s easier to wrap oneself in work, ideology, and compulsion than it is to be vulnerable and to belong. What appears to be courage reveals itself to be a frequently fatal fear.

The possessed represent for us many things — ideals, extremes, taboos, single-mindedness we can’t afford, personal asceticism we can’t abide, a lack of courage and self-awareness we can’t tolerate. That’s why we marry, have children, form friendships, compromise, trust, and say ‘yes’ to the whole ride, regardless of our inability to like or control every dip and turn. Drugs, alcohol, and myriad other self-abuses are not the prices of imbalanced lives: they’re the band-aids and the crutches. They’re not the coping: they’re the obliteration.

Hunter Thompson chose to obliterate himself. I miss his voice. His death taught me the lesson of his life.

—

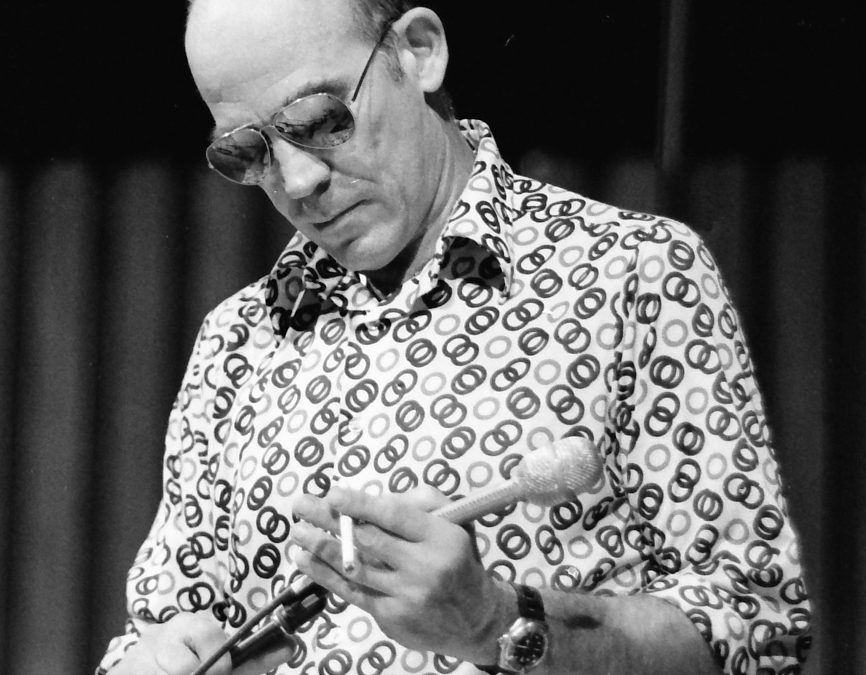

Photo by MDCarchives, cropped by Beyond My Ken, 31 August 2011, via Wikimedia Commons.