According to dictionary.com, hype is a derivation of hyperbole:

Origin: 1925–30, Americanism; in sense “to trick, swindle,” of uncertain origin; subsequent senses perhaps by reanalysis as a shortening of hyperbole

That’s easy enough to imagine. A hyperbolic pitch — especially for something of dubious value — is recognized for the ranting it is and dismissed as hype. Case closed, right? Not so fast.

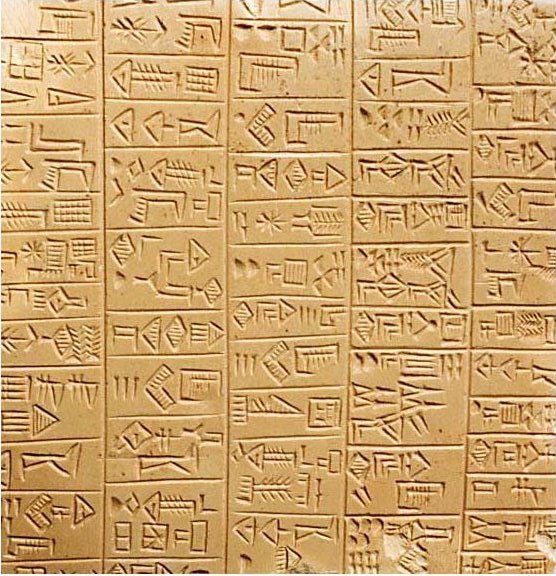

According to The Chautauqua Center for Business Etymology, hype turns out to be an acronym, comprising the first letters of the words in this phrase: hawk your personal enterprise. Its origins date back to stone tablets and the creation of glyphs. There’s academic dispute surrounding the first known instance of hype. But the archaeological, anthropological, and paleontological communities share this consensus, according to the Center’s report:

The first known person to employ hype was the Sumerian entrepreneur, Sargon Meskalamdug (“Sarge” to his friends), who used the tablet shown above to advertise his invention — the three-ring binder for stone tablets — in 3,300 BC. Early adopters found the binders convenient for organizing and storing everything from birth certificates to paid utility bills. But sales died due to the product’s lack of portability. Sumerians without access to winches and cheap labor were unable to transport more than a month’s worth of records even an inch. With the demise of that business, Sarge filed for Chapter 11; although, he later achieved wealth and fame as an early exporter of Mesopotamian barley to German brewmeisters.

Now, of course, hype is ubiquitous. Here’s just one example, sent directly to my Twitter feed from some apocalyptic chooch hawking his personal enterprise — a book full of gibberish about the end of the world (URL altered to protect the guilty):

Hey good to see you. An extract of my book is here tinyurl.com/doomandgloom.

See me? He doesn’t even know me. If you really want me to buy your book, woo me a little. Throw me a slow curve, rather than the high heat. Share some content. Tell me why the end of the world is important to me, my business, or my grooming habits. Pique my curiosity about the event. Help me understand how agonizingly horrific Armegeddon will be. At least give me some packing tips so I know what I should plan to bring when the Big One hits.

Whatever you do, don’t try to sell me your book — or anything else — on the first date. Engage me. Interest me. Give me content that will make me fall in love with whatever you’re selling before I even know what it is. Make me so infatuated that I become the one who pursues you. All I want is what I want. And in the Bold New World of social media, this distinction is everything: I have to want to buy it. You can’t sell it to me, regardless of how much you hawk your personal enterprise.

Social media may not constitute the end of the world as we know it. (The jury is out.) But it does constitute the end of the marketing world as we communicated in it. Social media has taken the buyer’s market out of the realm of the proverbial and made it the new reality. We’ll embrace it by its self-written rules. We’ll dump the hype in favor of the content. Or we’ll be apocalyptically lonely. So will our businesses.

—

Image by Schøyen Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.