Every year, in the eight weeks between Christmas and Valentine’s Day, a number of things can be counted on to take place. Each is a measure of our inexplicable humanity:

First, the holiday season will vanish, leaving us to realize our spirits are none the kinder, fuller, or more generous than they were last year and to wonder what constitutes the bigger mystery: That hearts dead from distraction and routine, empty and indifferent, can be brought to joyous life, made full to beneficence by the contagious, communal majesty of a Christmas Eve service? Or that those same, full hearts can be so quickly and completely desiccated, dead as dust in the reflexive resumption of the world’s hostile, unforgiving business?

Second, Martin Luther King Day will come with the renewed hope that we can understand and stop harming each other. It will pass with renewed disillusionment and the realization that we cannot. We will, again, pick up our guns, our stones, our pens, our voices, and resume the incessant vitriol that marks us human. The best intentions, the sincerest wishes, the costliest sacrifices will be lost in the Law of Large Numbers: If more people are angry and reactive than reasoning, patient, and willing to negotiate compromise, the angry and reactive will prevail.

Third, the tab will come due for all the holiday cheer we purchased, including payments deferred for gifts on which we over-spent, diets abandoned for meals we over-ate, hangovers staved by hair of the dog to keep us primed for every party of which we had to be the life. Our bank accounts dwindle while our bodies bloat. Our judgment falters as our minds fog and our livers shrivel and harden. Our gaiety becomes increasingly forced as it becomes further mortgaged.

Finally, there will be a Super Bowl. This mockery of gamesmanship will take place because our abilities to rationalize and our determination to deceive and entertain ourselves have no limits. By the time the players are lined up for kick-off, millions of us, variedly assembled in chairs, couches, family rooms, and bars all across the Land of Opportunity, will hold our breath, our wagers, and our disbelief, firm in the conviction that the hapless exercise we are about to witness might actually be a contest.

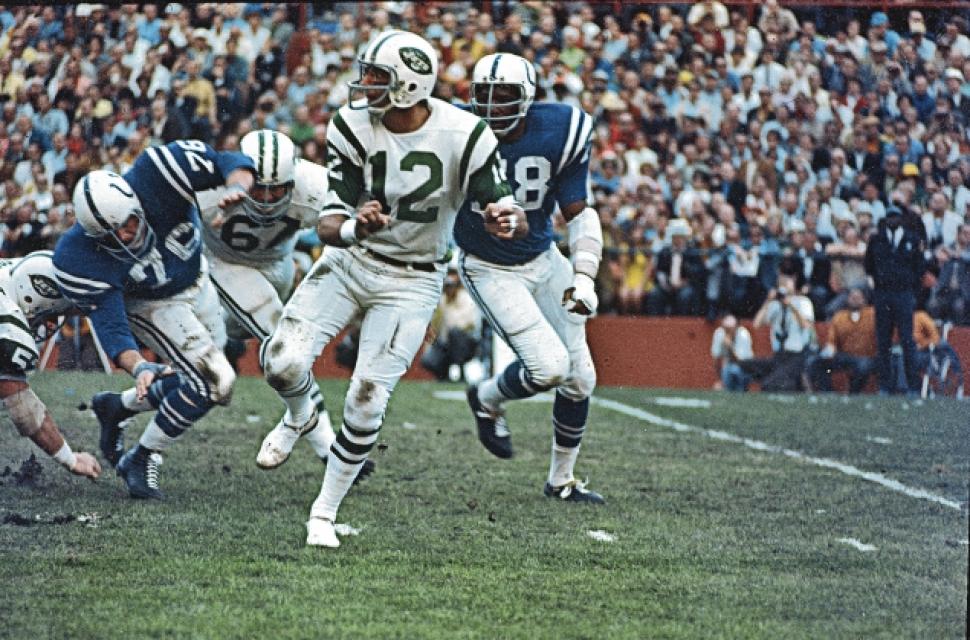

In a singular concession to our naiveté, by the same stubbornly hopeful innocence that allows us to believe in Santa Claus and the other fleeting miracles of the Christmas season just past — in the ardor-inducing magic of roses and chocolates on Valentine’s Day — we’ll convince ourselves the game has meaning. Like the back of Sisyphus bending under the rock, Joe Willie Namath’s already stooped shoulders bow more each year for lugging the load of the dream he made manifest in his Jets’ 1969 victory over Don Shula’s Colts. We, too, know the painful weight of sustaining dreams. But on we push.

In weighing salary caps, binding arbitration, ticket prices, schedules, expansion teams, rules, re-plays, referees, and the myriad minutia of the game, I wonder if NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell ever thinks about the Super Bowl this way. And I wonder if perhaps, by this absurdly brutal sport made ridiculously Big Business — having ridden out one year’s disappointments but looking straight into those of the next — I wonder if we don’t somehow redeem ourselves by this annual rite.

Hopeful, resilient as children, we turn on The Big Game. The interminable pre-kickoff advertising space becomes, not a test of endurance, but training camp, the re-birth of our hope and our prospects, the starting point, the New Year, the time at which, with no losses on our records, we can choose to believe (or believe we can choose) whether we will win or lose. Millions of us, in a hush not heard since Christmas Eve, are compelled, as one, to hope. Wow! NFL Charities never intended anything like this.

Maybe, after tragedy upon disaster upon calamity, after another year of avoidance and denial, this high-stakes contention over a pigskin is an indication of faith. Maybe our bestowal of credence on professional football — a commercial product, and a cynical one at that — is evidence of the inherent good by which we continue to hope for the hopeless. Maybe it’s some (any) measure of the possibility that our capacity for hope might endure.

And maybe, just maybe, if we allow it to, the charade we’re determined to see as The Big Game might remind us why we need heroes to believe in:

Even if those heroes are gone or imagined — Joe Willie, Santa, and Sisyphus —the hope they inspire is real. On we push.

P.S. In Super Bowl III, Sisyphus took the Jets and the points.

—

Image courtesy of the Associated Press.