More than 20 years ago, I worked for The Travelers. That’s right: In those days, it was called The Travelers, as opposed to Travelers, it’s known today.

I worked in the division that sold health insurance. That’s right: In those days, it was called health insurance, as opposed to healthcare, as it’s known today, now that politics, special interests, an appalling lack of business sense, an absolute lack of underwriting acumen, and deliberate ignorance of the Constitution of the United States have made it an inalienable right. (See “Disaster, The Obamacare“) But I digress.

During my tenure at The Travelers, I had occasion, for the first time in my life, to work for a man who was younger than me. We’ll call him Spike. Brought up from Dallas to World Headquarters in Hartford, Spike was reputed to be a change agent, a go-getter, a guy who’d turn The Travelers’ struggling health-insurance operations around in no time — rally the troops, boost sales, lift morale, put some fire in the corporate belly, and shiver some timbers.

At the same time, I happened to find an article from the April 1968 edition of The Atlantic. Entitled, “How Could Vietnam Happen: An Autopsy“, authored by James C. Thompson, the events it described paralleled what I was witnessing at The Travelers. And I would have sworn Mr. Thompson had met Spike when, in citing the deliberate purging of competence from the ranks of our foreign-policy makers during the Vietnam War, a purging that unwittingly led us deeper into the military/political quagmire, he wrote about:

… the replacement of the experts, who were generally and increasingly pessimistic, by men described as “can-do guys,” loyal and energetic fixers unsoured by expertise.

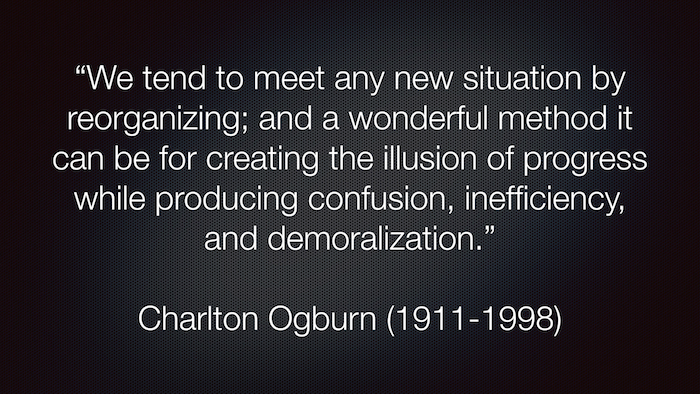

That was Spike. A loyal and energetic fixer. A guy who who couldn’t see a thing beyond the quarterly numbers he’d never achieve, who thought he could precipitate productivity from fear and intimidation, who shook up things and people and didn’t care what or whom fell out, who didn’t know what he didn’t know, who couldn’t recognize the hubris that would cost him his job and his marriage, who slapped Band-Aids on systemic diseases, and who couldn’t see he was a symptom of the Corporate Cancer that had already turned terminal.

Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it. (George Santayana)

Regardless of our occupations, we have just one job: to live, to learn, to experience, and to retain the lessons of experience.

In a world full of Spikes, who remain arrogantly unsoured by expertise, it gets harder and harder to do that job, even as it becomes more and more important to do it.