In a blog post I published a few weeks ago, I wrote this:

Once the organization — any organization — is large enough, no one needs to care about anything. Executive functions (making policy) are separated from work (conducting the activities that generate the revenue that pays for the overhead of which the policy-makers ultimately are a part). Thoughtlessness and lack of accountability are compounded by anonymity and invisibility. The hand-offs begin. And the reason no one cares or has to care is that the impenetrability of the bureaucratic pettifoggery is absolute. As long as the right people go through the right motions to keep the right people happy, the status quo is preserved.

Maybe my aversion to bureaucracy stems from the fact that I was 28 years old when I got my first corporate job. As a new college student at the same age, I was hired, part-time, by an insurance company. I worked in a unit that rated automobile policies. And our specific job was to update procedure manuals. And in those days, they were real manuals, typed on real paper, on real typewriters, and kept in the all-too-real three-ring binders that were absolutely everywhere.

As the son of a Marine — and as a guy who’d been a hospital orderly, a truck driver, a clothing salesman, and a worker in an appliance warehouse before going back to school — it wasn’t all that paper and all those binders that struck me as so wrong. No. What stuck irretrievably in my craw and remains there to this day is the wasteful inefficiency and unaccountability of large organizations.

Bureaucracy 101

One of the first things I learned from that job is that there’s only one person in every large, bureaucratic organization who actually does what needs to be done. Everyone else is just buzzing around, creating the appearance of activity. I learned that one day when one of my co-workers reported that the CEO wanted to streamline one particular procedure. I enthusiastically exclaimed, “Let’s do it!”

The group looked at me as if I were equal parts pitiful and dangerous. One of my co-workers said, with hushed astonishment and a fear of something that made her voice quaver: “But we can’t do that.”

Perhaps the concern I heard in her voice was some genuinely magnanimous regard for the job security of that one person who actually does what needs to be done. I never found out. But what I did find out is that, in any bureaucracy, you can’t just do anything. You have to follow the process. And everyone who utters the phrase, the process, says it with a reverence people usually reserve for their religious convictions or Oprah.

The Process

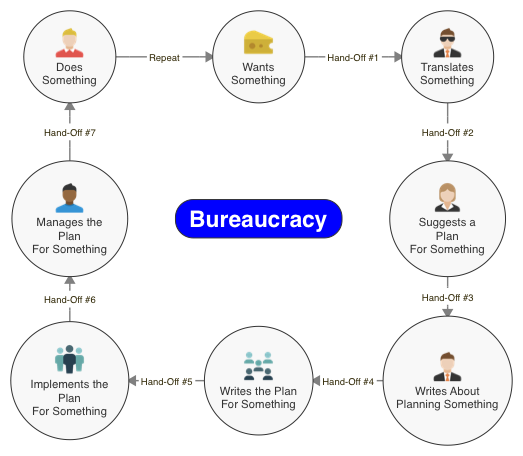

At risk of being excommunicated, here’s a step-by-step explication of how the process works (please refer to the graphic above for visual support):

- The Big Cheese comes up with his newest Big Idea for keeping the shareholders off his back.

- At Handoff #1, the Big Cheese tells the CTO (Chief Translation Officer) the Big Idea in the vaguest terms possible.

- At Handoff #2, the CTO wrongly explains the Big Idea to the CSO (Chief Suggestion Officer).

- At Handoff #3, the CSO calls the CIO (Chief Initiation Officer) and leaves a garbled voice mail about the Big Idea.

- At Handoff #4, the CIO drafts a 50-page document to get the CPC (Chief Planning Committee) started on a plan for actualizing the Big Idea.

- At Handoff #5, the CPC hands a two-page plan to the CIT (Chief Implementation Team) for putting the Big Idea into play.

- At Handoff #6, the CIT drops the Big Idea into the lap of the CMO (Chief Management Officer) to oversee.

- At Handoff #7, the CMO gives the Big Idea to the CHL (Chief Hapless Lackey), wishes him luck, and washes his hands of the whole mess.

- The CHL does the best he can with nothing, knowing he’ll either get shit-canned — or receive a CPA (Champion Performer Award). There’s never any in between.

- The process repeats endlessly with every Big Idea from the Big Cheese. And despite press releases to the contrary, nothing ever changes.

Moving On

I spent 13 more years toiling in the invisible anonymity of corporate bureaucracy. I moved from the company in which I worked at 28 to two others. In each of them, the solemn allegiance to the process remained immutable. In all of them, the process triumphed over initiative, directness, resourcefulness, imagination, creativity, ambition, efficiency, critical thought, and common sense. And in every one, it was more important to do things right than to do right things. I was an older, wiser, sadder, and considerably more jaundiced 41 before I finally moved on and out.

Was my experience typical? With all of the compassion I can muster, all I can say is: I hope not.